Open Cities 36 Open Economic Recovery?

Open Cities: Milestone

On 25 May 2011, URBACT, the British Council, the Open Cities Network and the Open Cities project partner cities congregated at the premises of the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions in Brussels, Belgium, at the conference on Open Cities and Economic Recovery, the closing event of a three year project initiated by the British Council and supported by URBACT II.

It was a privilege and a pleasure to have been asked by the British Council to become one of its ‘official bloggers’ on its Open Cities website and to contribute my own thoughts towards this very timely theme. Here are my personal views about what this undertaking initiated by the British Council and supported by EU URBACT II has achieved and where it could go in future.

The project is now standing on its own feet. The British Council has reduced its Open Cities website to information on the Open Cities Monitor and on the local action schemes initiated by the participating cities with the EU URBACT II grant. My commission as ‘official blogger on Open Cities’ is coming to an end. However, I consider the theme of Open Cities very topical and will continue an Open Cities blog on my own website <www.urbanthinker.com>. I will observe how the participating cities are implementing their local actions plans and what effects the Open Cities Monitors may have on cities becoming more open. Most importantly, my blog will focus on Open Cities issues where they are arising, especially in places where I have first hand experience.

Openness in a world of plentiful

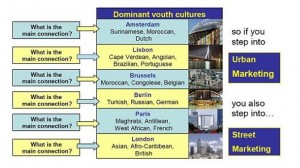

The open cities project originated at a time of optimism and expansion, when flows of migrants were swelling European cities and contributing to their growth and cultural vibrancy. Soon afterwards the world was changing. It got caught up in a global financial crisis, ill prepared to cope with it.

What started off as an inquiry into the impact of large scale drivers – economic globalisation, population mobility, technological innovation, climate change and governance – on the future welfare of cities has been narrowed down to a “new marketing category that can be used to promote their [cities] openness and raise their international profile”.

The concern with the contribution of cultural diversity to both a city’s prosperity and welfare has been confined to how openness can become a “competitive advantage during recession”. Moreover, in a world fixated on economic output, developing a tool of quantitative measurement to capture how cities capitalise on migration was an obvious undertaking.

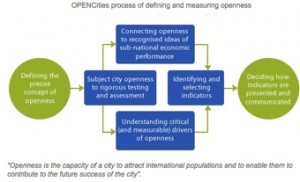

OPEN Cities Monitor

This tool of measurement, facilitated by the Open Cities project, is a device to establish a rank order of cities, assessing their ability to compete in a global universe through openness. The monitor is based on 11 sets of indices, mainly econometric, based on data compiled from 26 greatly diverse, fee-paying participant cities, ranging from medium size European cities to global capitals and megacities in the developing world. The monitor enables participating cities to position themselves in three main areas: internationalisation, leadership & governance, and managing diversity. The benefits are described as obtaining interactive snapshot analysis of openness, the use of the OPENcities brand, access to case studies and benchmarking progress of policy results.

It should be kept in mind that there exist many similar tools with far larger and statistically significant datasets. The the OPEN Cities Monitor has even modelled itself on some of them, such as the MERCER index which is aimed at global corporations.

Trying to quantify a concept as vague and as complex as ‘openness’ related to cities in monetary terms alone may prove overambitious, notwithstanding the usefulness of such a tool for everyday decision making in politically turbulent times.

The OPEN Cities Monitor may be the only tangible product to outlive the cooperation between 9 cities led by Belfast, Northern Ireland, whose initial aim was to understand what openness means in relation to cities, what it can bring to them, and how cities could become genuinely open.

Local Action Plans

Although ‘process’ seems to have gone out of fashion in city management the participant cities clearly benefited from comparing their approaches to intense influx of immigrants, and ways of harnessing their diversity while coping with challenges to social cohesion. The diversity of the “local action plans” devised by the participant cities shows how they adapted their routine actions to incorporate diversity and to promote openness by fostering good relations and trust within multicultural neighbourhoods. The conference confirmed that cities had benefited from sharing the experience of incorporating openness into their policies and practices.

Whether internationalisation is of equal importance and immigration an economic business imperative for all cities remains an unverified postulate. Nevertheless, managing diversity, diffusing latent conflict and unpacking real and perceived injustice are undoubtedly wise policies when urban populations are rapidly diversifying in cultural, ethnic and religious terms.

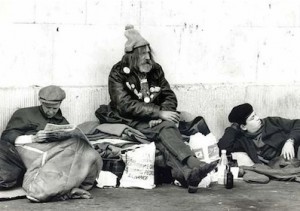

Focusing openness exclusively on immigrants may not be justified though. Open cities should address diversity among existing urban populations as well. Differences are increasing in many other spheres, most drastically in economic conditions. Considering that the gap between the 100 FTSE executives and average earnings of their employees has increased from 45 times in 1998 to 128 times in 2010 (Anthony Hilton, Evening Standard 23 June 2011, p44), is a harrowing statistic, and possibly a much greater trigger of social conflicts than women wearing a veil. The white elephant in the room is class, a great divide in many urban societies. Sometimes it is correlated with minority status, but these relations are in flux and lead to many paradoxes which affect openness. The set of concrete recommendations reached by the project (see Open Cities Fact Sheet 2011, URBACT, pp 6-8) are not new and apply just as much to urban development strategies in general as to migration issues. This is not the place though to deconstruct them into concrete interventions and uncover that such general objectives may not command consensus across all cities.

Legacy

It is important to stress that the Open Cities project has left a rich legacy (for details see www.urbact.eu/opencities and www.opencities.eu). Hopefully the local action plans will be implemented and the city network will remain a vibrant instrument of knowledge creation and sharing and will endeavour to archive and disseminate widely the outcome of their many events, exhibitions, experiments, educational material, publications, surveys, newsletters and blogs towards making their cities more open.

I reiterate that I will continue to write on open cities on www.urbanthinker.com. The purpose is to share useful information and experiences as a basis of interaction towards a very much needed, dynamic understanding and improvement of city openness, hopefully among an ever increasing network of cities. Many questions remain to be explored.

‘Openness’, a moving target?

Immigration is an old phenomenon worldwide. European cities have always received, lost and rejected new groups of outsiders for a wide variety of reasons. Arguably, scale and intensity of migration have more relevance as regards the robustness of openness than provenance or type of immigrants. Immigration does not have the same effect on all cities of all sizes in all places. Thus, openness is context-bound and needs differentiation.

Debates on openness have a tendency to concentrate on race and religion. Yet, if open cities imply less segregation and discrimination, they have to address a far wider range of social and spatial (in)justice. At the outset of the Open Cities project, openness encompassed cultural, educational and social activities but the project was soon reduced to how to attract immigrants to accommodate demand of modern firms, investors, visitors and traders (Greg Clark (ed). 2008. Towards Open Cities. British Council p11). The impact of the economic crisis on cities reduced the rationale of openness to economic recovery.

Trying to maintain openness during an economic crisis may stir up conflictual processes. What was always present under a surface of shallow cohabitation may surface as ‘scape-goating’, resentment against foreigners, (re)invented indigenous traditions, imagined identities, and oblivion of long standing interdependence between minorities and majorities.

What next?

The Open Cities project has lifted the cover of a very complex and paradoxical contemporary urban phenomenon. There is a long way to go.

Social and spatial (in)justice, democratic deficit endured by immigrants who fulfil their civic duties without being able to exercise citizens’ rights, who are without a voice other than as outsiders or dissidents have not been addressed in the open cities project. These issues are bound to move centre stage once austerity measures are starting to bite in earnest and may well become the core test of cities’ openness.

Similarly, concentrating on diversity and integration of outsiders to the detriment of inequalities and injustices within makes for an explosive situation, even more so during times of hardship and may well need greater attention.

There are still many experiments to undertake and share to gain a true grasp of what openness in urban life actually means, how it can be managed, if at all, and whether all those who live, work and play in cities can be motivated to take ownership of such an integrative project.